5 facts you might not know about ANZAC Day and its history

21 March 2025- ANZACspirit

- History & commemoration

Discover five surprising facts about ANZAC Day, from the first shocking reports of Gallipoli to the soldiers who captured history with their own cameras.

1. Australians were unprepared for the staggering loss of the Gallipoli landing

Australians were shocked when the first reports of the Gallipoli landing appeared in newspapers in May 1915. The nation’s previous experience of war had been the Boer War (1899-1902), during which approximately 600 Australians were killed over three years.

In 1915, it was inconceivable that these losses might be exceeded so early in the Great War. Initial reports from the Dardanelles warned the public that “the Australian casualties are extremely heavy… [with] a fairly high total of killed and wounded”. However, nothing could prepare the public for the shock and disbelief that followed as newspapers reported a steady rise in casualties over the following weeks.

By 5 June 1916, just six weeks after the landing, 750 Australians had been killed, 4,803 were wounded and 51 were listed as missing – more than the total number of Australian casualties during the entire Boer War.

ANZAC Beach, Gallipoli, 1915

2. Most photos from Gallipoli were taken by the men who fought there

As Australia’s official war art scheme had not been implemented when the 1st Australian Imperial Force occupied the Gallipoli Peninsula, there was no official photographer assigned to the campaign. Consequently, most images of Australians at Gallipoli were taken by the men who fought there.

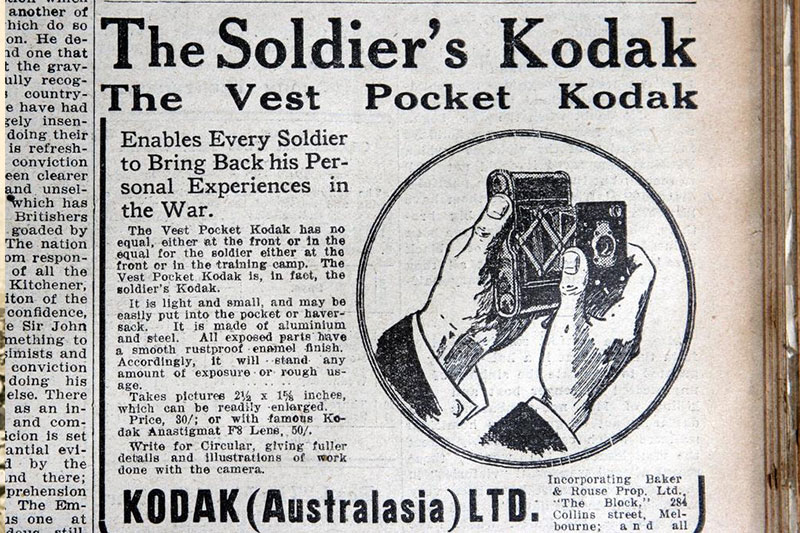

In 1912, Kodak introduced a folding camera small enough to be slipped into a vest or coat pocket. These compact devices quickly gained popularity during WWI, with many soldiers and nurses using them to record their memories and experiences while serving abroad.

Many of the men who fought at Gallipoli tucked a ‘soldiers’ camera’ into their tunic pockets before landing in 1915, and thanks to their interest in photography, we have enduring images of the famous event.

A Kodak advertisement from The Weekly Times in 1915 | Image - Herald Sun Image Library

3. Many ANZAC Day rituals evolved from existing commemorative practices

After the Boer War, communities around the nation banded together to erect monuments to remember their fallen. These war memorials became the focus of community commemoration in the years that followed.

Often, the monument and nearby area was swathed in bunting. The Union Jack and/or Australian flag was flown and the community gathered for a short religious service.

Hymns were sung, bands played music and wreathes were laid by families of the fallen, veterans and community members. Politicians frequently attended, together with other civic dignitaries and representatives from a state’s ex-service organisation: the South African Returned Soldiers Association.

The Last Post sounded, often followed by a parade or march past featuring returned men, serving Army members and other community groups. During and after WWI, these traditions evolved into the foundation of ANZAC Day.

An estimated 2,000 people attended the seventh annual South African commemorative service in Melbourne in 1913. The Australasian

4. The men who marched in the 1916 ANZAC parade in London were selected for their “fine physiques”

Fifteen years after Federation, the 1916 ANZAC parade in London offered Australian officials the opportunity to celebrate and showcase the young nation’s military prowess. Sunny weather and clear skies ensured maximum crowds for the event and journalists reported that “the fine physique of the colonials attracted universal attention”.

However, while Australian (and New Zealand) troops drew admiring glances from locals and gave rise to the early evolution of the tall, square-jawed ANZAC stereotype, the diggers were far from impressed.

Some complained that their shorter comrades were excluded from the parade in preference for “giants… some of whom had never been to Gallipoli”. To make matters worse, the men who landed at Gallipoli were relegated to the rear of the procession while the Australian Light Horse – who arrived as reinforcements in May 1915 – took centre stage by leading the parade.

Australian troops march through London on ANZAC Day 1916. | Image - Museums Victoria Collection

5. Is it an ANZAC biscuit or an ANZAC cookie?

It is most definitely an ANZAC biscuit. The name, recipe and shape of the iconic biscuit are protected by government legislation and must not deviate substantially from its generally accepted recipe or traditional shape.

If a commercial business wishes to call a product an ‘ANZAC biscuit’, it cannot add other ingredients (such as chocolate or nuts) or change its name. The only recipe modifications allowed are substitutions to cater for dietary restrictions.

For example, for dairy intolerances, a non-dairy substitute can be used without affecting the ability to call the morsel an ANZAC biscuit.

But what if you have a fondness for adding macadamias to your homemade ANZAC biscuits or enjoy dipping them in chocolate? Don’t despair; the guidelines only apply to the commercial production of ANZAC biscuits and not personal recipes, recipes posted on social media or those contained within general recipe books.

Try making your own with our classic ANZAC biscuit recipe.

This ANZAC Day

ANZAC Day (25 April) is a time to recognise all who have served our nation, and their invaluable legacy.

Wherever you’ll be on ANZAC Day, please join the community in attending a commemorative service.

There’s no greater way to honour those who have served.

*Hero banner image - Australian soldiers assembling in line prior to taking part in one of the first ANZAC Day marches through Cairo to commemorate the first anniversary of the landing at Gallipoli in 1915.